Something people in the search engine optimization space often repeat is, “make sure your website has a good link structure.” Rarely does anyone explain what that means. We’re often told that a good link structure is very flat, so that any page isn’t too many clicks away from the homepage. But why is that valuable or useful?

Flat site structures are good for users because they can get anywhere on the site fairly quickly no matter which page they land on, but there is also an algorithmic reason for having a flat structure. Generally, flat websites distribute more PageRank to important pages than deep websites because they are close to the homepage.

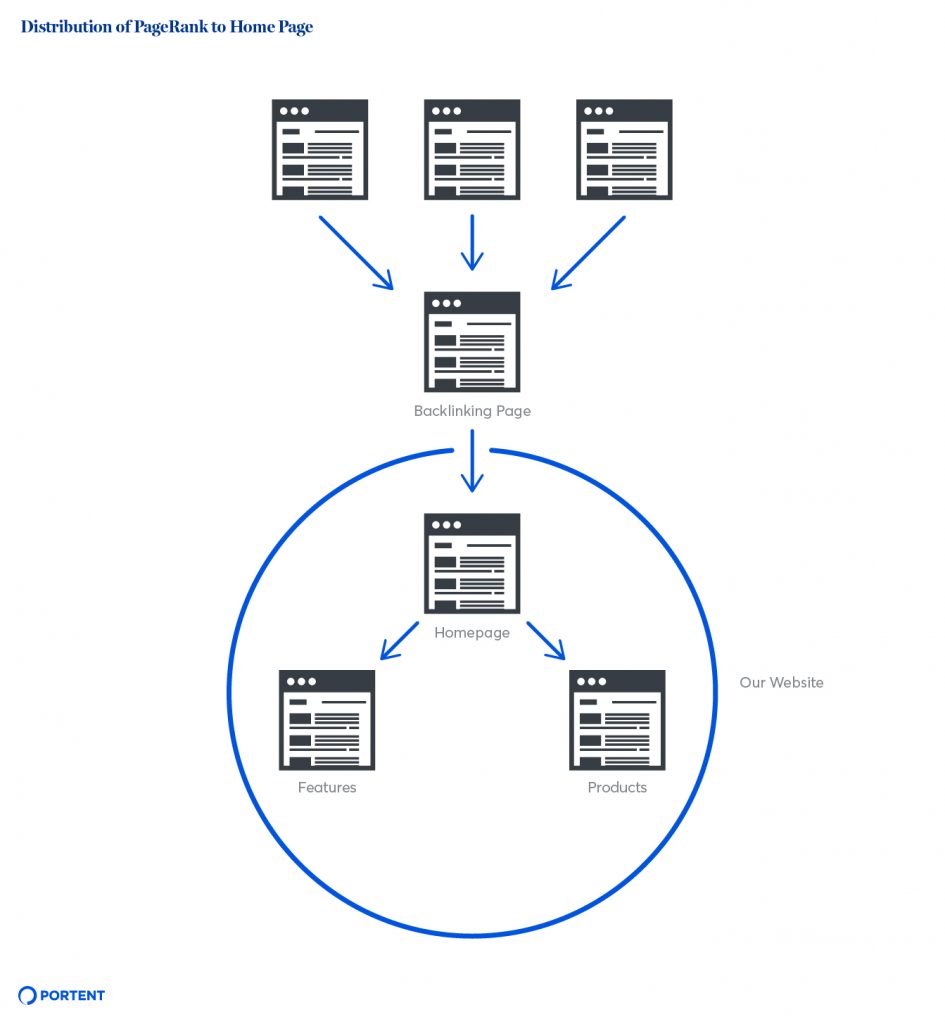

What makes the homepage special for PageRank is that most websites receive backlinks that point to their homepage more than any other page. If the homepage receives the most PageRank from the rest of the web, then most of that PageRank is distributed to the pages the homepage links out to. Pages that are one click away from the homepage tend to have the second-highest amount of PageRank, and the pages they link to tend to have the third-highest PageRank, and so on.

What do we do if we’re working on a website that doesn’t have a flat link structure? If we have an important landing page and it’s four or five clicks away from the homepage, then we’re going to have a harder time because of how little of the external PageRank is being shared with it.

To help pages like this rank, we’re going to need to reroute how PageRank flows on the website a bit using some internal PageRank optimization strategies. This guide contains best practices, reporting, and an implementation process to get the most out of the PageRank flowing into our websites.

A Short Primer on PageRank

PageRank was Google’s first breakout algorithm. Named after Larry Page, it was a culmination of his and Sergey Brin’s original research at Stanford to extract something useful out of the link structure of the web. They found that pages that receive links from pages that receive a lot of links tend to be of higher quality.

Incorporating this quality signal in their results gave the Google search engine an early edge over their established competitors. But why would the link structure of the web have anything to do with quality? People tend to cite, recommend, and share content they found to be useful. Organizations with editorial policies like newspapers, governments, and schools will pay closer attention to whom they link out to, so vetted links indicate higher trustworthiness and authority.

How PageRank works is pretty interesting from a mathematics and computer science point of view, but we don’t need to get into all of the specifics. Pages tend to have high PageRank if they receive links from pages with a lot of links, and those pages receive links from pages with a lot of links, and so on.

Whatever PageRank looks like today is probably very different from Google’s early research and patents. The calculation method, how links are weighted, and which links are included are definitely different. Google has a patent for PageRank that depends on the position and context of links, a patent for a “seeded” PageRank, and how Googlers used to talk about topical PageRank.

This article will talk about modeling PageRank over single websites instead of the whole web, and using the classic formula. Is that useful at all based on what we know? Anecdotally, I have found this approach useful and have had success with it. This leads me to believe that whatever link-based signals in the production algorithms are affected by local link structure, and classic PageRank is a pretty good compass for improving that local link structure.

Strategies for Improving Link Structure

In general, the way to improve a page’s position in the link structure of the site is to link to it from pages with higher PageRank, or link to it from lots of smaller pages.

Here are some strategies to do that:

Strategy 1: Create Big Links

We want to find instances where a few small changes will have a huge impact. One “big” link from a higher PageRank page can put a page over the edge and onto page one of SERPs.

- Is our target landing page important enough to warrant a spot in a global navigation? Some pages, like key product and service pages, are passed over when the main navigation was decided on. Adding them will distribute more PageRank and help users find them easily.

- Maybe it makes sense to add it to the homepage or another tier-one page with a contextual link.

- HTML sitemap pages are a great place to add pages that need more link love. Since HTML sitemap pages tend to be linked by every page in the footer, they accumulate a significant amount of PageRank.

Strategy 2: Create Lots of Small Links

Enough small improvements build up, and so does PageRank. We want to add links to many tier-three and below pages in a way that’s relevant and useful.

- Create content hubs by linking to a target page from any other related page. Connecting relevant content through links will also help with relevance and direct users on the site.

- An easy way to find pages to add to a hub is to search for things like “topic site:domain.com/blog” in Google. The site: operator results will surface pages on your site.

- Add a sidebar for trending or top content to your blog to get links from every other page in the blog section.

- Add a related content section to your blog posts to automatically crosslink pages about the same topic. Some plugins for this allow you to choose which links appear on a page.

Strategy 3: Place Links on Pages With High External PageRank

Some of our pages are naturally going to receive links from other sites, and we can distribute that incoming PageRank to our other pages.

- Create an inventory of pages with lots of external links and refer to it when optimizing your content.

- See a guide to this in the next section.

Strategy 4: Make More Pages Count

An often overlooked way to improve the link structure of the site is to make key pages indexable. Many SEOs are still adding noindex tags to pagination pages, tag and category pages, and faceted navigation pages in an effort to reduce “thin content.” These pages have a very important role on the site and should be indexable in many cases.

- On sites with hundreds of pagination pages, a blog post might rely on a pagination page that is 25 clicks away from the homepage for its only internal link. Category, tag, and author pages are effective ways to provide an alternative click path that is much shorter. So long as tag and category pages are well-formed and useful as navigation for users, they should be indexed.

- The number of possible combinations of filters and options in a faceted navigation can explode, causing a crawl budget problem. Some SEOs handle this by making every filter unindexable, but they are unnecessarily limiting how many viable landing pages they can use.

- By carefully controlling which filters are indexable in a faceted navigation, the number of combinations can be kept to a crawlable level while providing URLs that can act as landing pages. For example, if a subcategory for men’s running shoes has a color filter, the filter URLs for black shoes and green shoes should be indexable, but the URL for black or green shoes does not. Similarly, filter URLs for black shoes and sort ordering or price don’t need to be indexable either.

Strategy 5: Take Advantage of Your Other Websites

Big brands tend to have more than one site they own, and they are often overlooked for optimizing PageRank. Common examples are investor relations websites, career subdomains, websites for parent or subsidiary companies, and external blogs.

- Find ways to add links to these websites that are useful and relevant to your users, such as adding links to the footer navigation, or creating a hub of subsidiary brands.

- One website that does this well is J2 Global with its portfolio hub.

- Something Amazon has done for a long time is add almost all of their brands to their footer with a tagline in the anchor. This is an extreme example, and they definitely have enough PageRank to pass around, but most brands could get away with listing a few of their siblings.

How to Check Internal PageRank Distribution

Before we start changing our links around, we need to know if there are any pages with a problem. We want to know if the pages we think are important are receiving a commensurate distribution of internal PageRank. To do that, we will need a way of calculating PageRank over just the pages in our website and not the whole web.

Portent has a proprietary crawler called RainGage that we use to analyze our client’s websites. One of the features Matthew Henry built is an internal PageRank modeling tool that calculates the PageRank score of each crawled page using a formula very similar to what Google described in the classic patent.

Unfortunately, RainGage isn’t a public tool, so not many people get to use it. Other commercial tools calculate PageRank in a similar way, but the most accessible one is Screaming Frog.

Estimating Internal PageRank With Screaming Frog Link Score

Screaming Frog has a metric like PageRank they call Link Score. It is fairly easy to get, but the feature is hidden away a little. They have a guide to Link Score here. To get Screaming Frog to show Link Score for URLs in a crawl, you have to run Crawl Analysis after the crawl completes.

Internal PageRank distribution is primarily determined by the link structure of the site. Our important hub pages tend to appear in the main and footer navigations of our website, causing them to receive links from every other page on the site. If you look at your link score report, you’ll probably find that the pages in your global navigations have the highest scores. We’ll call these the tier-one pages.

Pages that receive links from tier-one pages or a sidebar navigation somewhere tend to be in the second tier of PageRank distribution. Tier-two pages tend to be subcategory pages or hub pages not important enough to make it into a global navigation.

Tier-two pages tend to link to tier-three pages—those pages that are the better-connected leaf pages in the tree structure of the site. They look like products, services, blog posts, industry pages, and whitepaper pages that are part of the primary user journeys of the site.

Bottom-tier pages tend to be those relegated to receiving links from pagination pages: blog posts, product description pages, press releases, whitepapers, webinars, data sheets, etc. Since they only receive links from pagination pages or tag pages, their link scores are going to be pretty low.

Creating a Content Inventory With Link Score

To see how our pages are positioned in terms of internal PageRank distribution, backlinks, and conversions, we’re going to add data to our list of URLs and Link Scores. This inventory will help us later when looking for pages that need their internal links improved, or have good internal or external PageRank they can share.

- Export the Internal pages report from Screaming Frog, load it in your favorite spreadsheet program, and pare it down to the link metrics you care about.

- Next we need some idea of external PageRank for the URLs on our domain. Go to Ahrefs (or a similar tool) and export the Best Pages by Incoming Links report.

- Join the columns for URL Rating (Ahrefs’ approximation of external PageRank), referring domains, and dofollow links to our table using vlookup, index-match, or any other lookup function in your spreadsheet app. You can also sum the dofollow and nofollow links from Ahrefs, as nofollow is now just a hint to Google.

- Go to Google Analytics and export a landing page report with traffic (sessions or users), conversions, conversion rate, and revenue if available. Join those to the inventory we’re constructing. Use a date range that’s appropriate for your purposes or representative of the performance of your pages. I’m using one year of traffic here.

We’re going to use this inventory sheet to find instances of:

- Pages with higher conversions or revenue, but low Link Score. We’ll be creating links that point to these pages.

- Pages with low conversions or revenue, but high incoming PageRank from outside the website (high URL Rating, referring domains, and backlinks). We’ll be creating links on these pages to spread the external PageRank out to other pages.

- Pages with low conversions or revenue, but high Link Score. We’ll be creating links on these pages to share their internal PageRank with other pages.

Improving PageRank With Internal Link Creation

As you find opportunities to add individual links, having a way to keep track of them is pretty handy. I’ve been using a spreadsheet template to keep track of the links I want to place on the sites I work on. Here is a template you can use.

The process I use with this spreadsheet generally follows these steps:

- Find a page that needs a boost to its internal PageRank. Refer back to the content inventory we made in the previous section to find good candidates. Alternatively, I’ll work on sets of pages according to campaign, season, or priority.

- Get a list of the page’s target keywords. If you’ve already done keyword mapping or have a ranking report, then refer to that. Otherwise, put the page’s URL in Google Search Console and see which keywords it receives clicks from and could rank better for.

- Find pages to place links on. Refer back to the content inventory for the pages with high internal PageRank or high external PageRank to see if any are relevant to the page you want to point links to. Doing a Google search for “topic site:domain.com/blog” will find blog posts on your domain that are relevant to your page’s topic.

- Figure out placement for the link. The context of a link is something Google has been looking into for a while. Google’s Reasonable Surfer Model patent indicates Google has been looking into ways to assign weights to how links pass PageRank based on how likely a user is to click on them. Google has likely also looked for ways of identifying when a link probably isn’t useful to users, so link to the page that makes sense to users and helps them out.

- Determine an anchor text for the link. Google uses anchor text to determine what a page is about, but they recommend using a “reasonable anchor text.” For us, that means the anchor text in our links should describe the page, support rankings of our target keywords, and help users know what they will find on the page. This is often not the same text as the keywords we want to rank for.

- Determine what content needs to be added or rewritten. Sometimes the text of pages needs to be reworked a little to make a link fit into it. Adding a description of how text needs to change to the spreadsheet is very helpful for anyone I pass the implementation off to.

Organizing the links you want to create like this also helps with getting approval, and tracking when the links go live to see if implementation correlates with performance gain.

Don’t Bury Your Landing Pages

Ideally, creating links to improve internal PageRank distribution shouldn’t be necessary. We would have already identified which pages need to rank the most and placed them in the information architecture of the site appropriately.

However, not every website is optimized like this from the get-go, and we’ll need to guide them in the right direction over time as sections are added and reworked.

Hopefully, going through this process will prepare you for when the time comes to redesign your website, and you’ll be able to recommend a site structure that favors the most important landing pages.

The post Internal PageRank Optimization Strategies appeared first on Portent.